A retired shell enthusiast recently donated thousands of shells to the Guam NSF EPSCoR Biorepository, many of which were collected on Guam during the 1960s, to be added to its historical collection.

Warren B. Carah, author and engineer, spent his teenage years in Guam from 1960 to 1964, when his family relocated due to his father’s service as an officer in the U.S. military. Carah attended Tumon High School, now known as John F. Kennedy High School, and spent his after-school hours searching for shells in Tumon Bay with his friends.

“We went to our lockers, got our spear guns out, and took the old Japanese elevator that went from the cliff down to the beach and we spent the rest of the day shelling, we went to just about every beach on the island,” Carah said.

Aside from Tumon Bay, Carah and his friends also frequented Apra Harbor, Malesso’, Cocos Island, and Tarague Beach in Andersen Air Force Base.

“I used to spend many, many hours out there at night. The bottom would literally be crawling with the very large cone shells, olive shells, and cowrie shells and during the day, it would look barren but at night, everything had come out,” Carah stated.

The donated shell collection includes around 4,000 shells from Guam, the Philippines, Australia, North America, and Africa.

Carah is aware of the difference in shell conservation now compared to how it was in the 1960s. “I think nowadays, most anybody that collects shells on Guam is quite aware of the fact that they have to let that resource go after they had found it, photographed it perhaps.,” Carah said, adding, “That didn’t exist in the early 1960s, but we still practiced conservation. There was no point in us collecting dozens and dozens of the same shell. We would collect one or two and our efforts would then go to find a new species.”

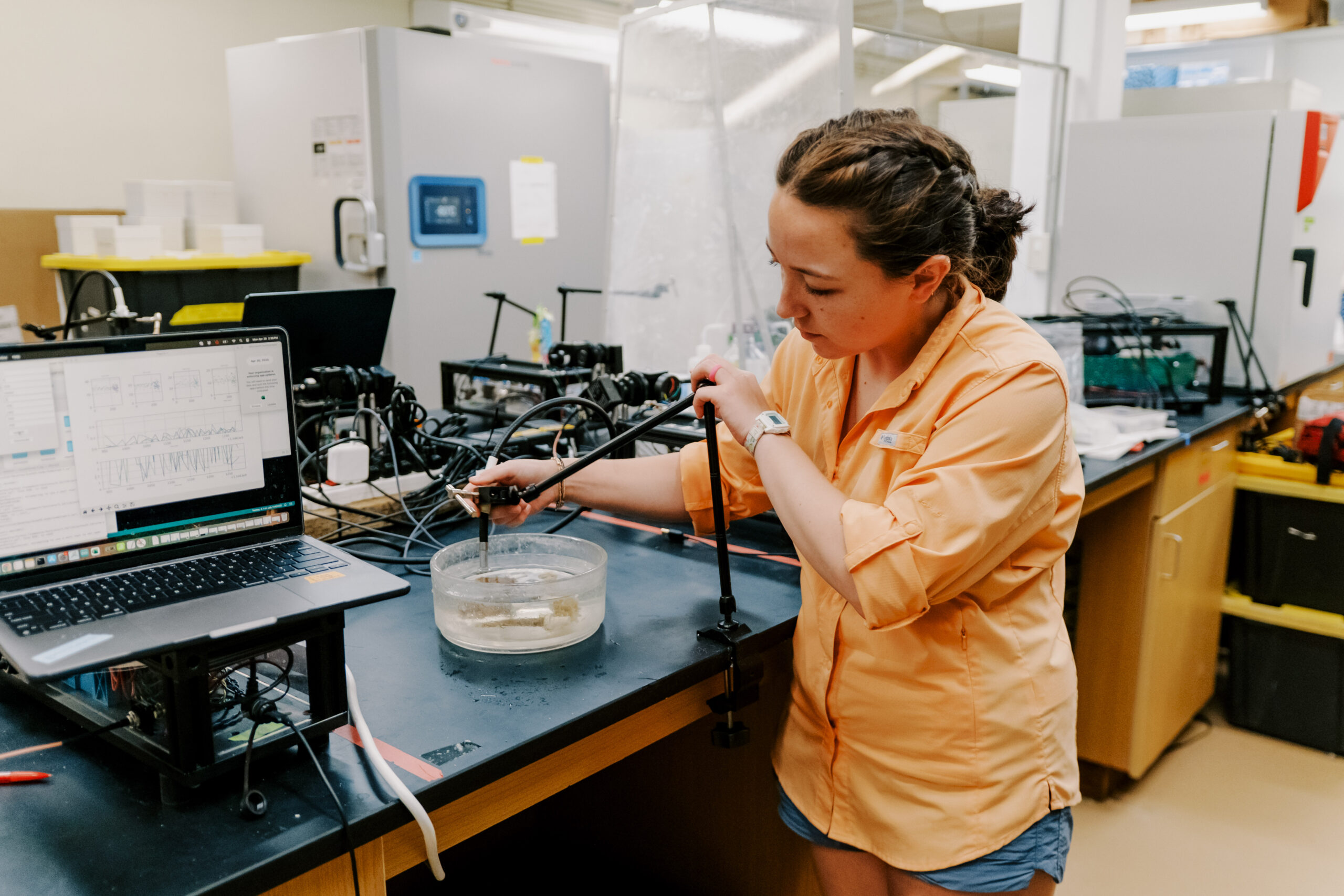

The Guam NSF EPSCoR Biorepository works to consolidate and expand Guam’s natural history collections and provides state-of-the-art digitization, imaging, and mapping of local and regional marine fauna and flora.

Regarding the importance of this donated shell collection, Robert Lasley, Ph.D., assistant professor and curator of crustacea at the UOG Biorepository, describes it as “valuable for establishing a historical baseline, as well as for studying different species to better understand Guam’s biodiversity. It also allows researchers to compare what may have existed in certain localities in Guam back in the ‘60s to what is being found now.”

Carah had been sitting on his shell collection for almost 60 years before ultimately deciding to donate it to a place that can benefit from its possession.

“I sent a letter to the dean of the biological sciences group there at the University of Guam and she evidently then turned that over to Dr. Lasley, and then he contacted me via email and we’ve been corresponding ever since,” Carah said.

Lasley stated that Carah’s shell collection includes the exact day it was collected and the precise location where it was gathered. “So he not only did these collections, but he kept a lot of good data and took really good care of them. In fact, you can see how well he packaged this stuff and sent it to us in really good condition,” he said.

The Biorepository houses thousands of coral specimens, crustaceans, fishes, algae, and other organisms to serve as an archive of the biodiversity found within the Micronesian region. Lasley explained that modern tools now allow for the collection and global dissemination of data from these specimens. He added that, eventually, all of them will be photographed, and their locality data will be gathered and entered into the curatorial database

“We’re going to get all the locality data from all these, and we’ll put them into our curatorial database, but then serve them online globally so any researcher anywhere in the world can access this information,” Lasley said.