UOG researcher discovers new diatom species in Micronesia

Christopher Lobban, a University of Guam professor emeritus of biology, has discovered an interesting new species of diatom from the Marshall Islands. His discovery is in addition to two potentially new diatom species found earlier this year by UOG student Gabriella Prelosky and five potentially new species by UOG student Britney Sison. The study, which was funded by the university’s National Science Foundation EPSCoR grant, was accepted in October for publication in the peer-reviewed journal Diatom.

Diatoms are single-celled algae found in oceans, lakes, and rivers. They are considered important primary producers on Earth. According to Lobban, diatoms produce an estimated one-fifth of oxygen in the air we breathe.

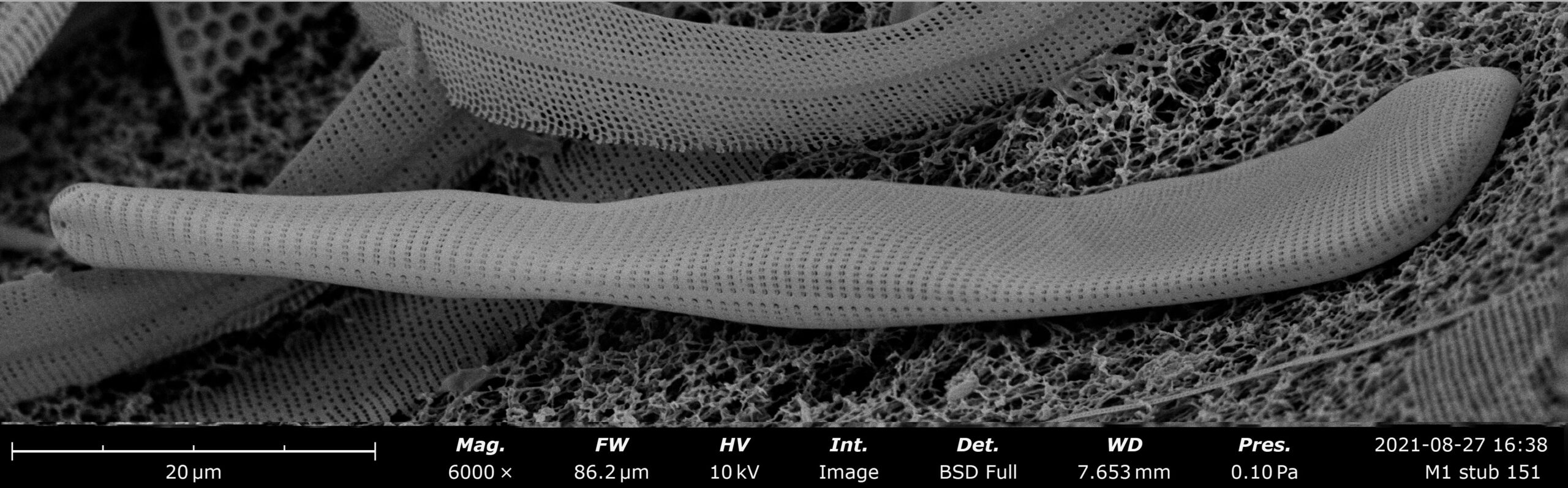

The new species of diatom, Licmophora complanata, was named for its flattened cell wall. According to Lobban, the diatom was found in a sample of algae from Majuro Atoll that he collected in 1990. Licmophora is a genus of benthic diatoms. Diatoms within this genus are common and epiphytic — meaning that they perch on seaweeds, like orchids perch on trees.

“It’s a really odd-looking Licmophora,” said Lobban. “Licmophora are sort of people-shaped. They have a top and bottom and a front and back. The dead shells can usually be seen in the front and back views, but this one was always giving me a side view.”

Lobban was able to thoroughly examine the specimen once the Microscopy Teaching & Research Laboratory, which he runs, received a new Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) through the EPSCoR grant in May 2021.

“The microscope has a stage that allows you to tilt it up to 80 degrees while examining a specimen,” said Lobban. “When I did that, I was able to see its shape, which is actually kind of complicated.”

According to Lobban, this is not the first time he has named a species of Licmophora.

“It’s not a huge genus and there are not many people working on it in the world. Most of the species here seem to be new to science. This is the 16th Licmophora I’ve named,” said Lobban, “and I’m not done with them yet. I’m working on a paper now with seven more species. It and several of the others have student coauthors.”

NSF Guam EPSCoR taps into the Open Science Grid

As research opportunities continue to expand for the University of Guam EPSCoR- Guam Ecosystems Collaboratorium for Corals and Oceans (GECCO) program, so does the need to improve its cyberinfrastructure to keep up with the additional computational and data analysis requirements.

Part of the UOG EPSCoR-GECCO strategic plan is to implement high throughput computing (HTC) resources in Guam and to establish partnerships that would broaden access to off-campus HTC resources. According to the plan, “leveraging existing partnerships to enable remote access to HTC resources, implementation of local HTC hardware and effective user support will accelerate UOG’s capacity for data-intensive research, moving UOG closer to its goal of becoming a research-intensive university.”

To beef up research computational capacity, the program is looking at tapping into the Open Science Grid (OSG). According to the strategic plan, the OSG will provide project research access to its distributed computing network to facilitate parallel computing and support GECCO research.

Jeffrey Centino, research computing facilitator at EPSCoR –GECCO said the OSG

is a collaboration between institutions, universities, and other research organizations to forward the field of science through high throughput computing.

“So basically, you have these data centers located around the world and they are connected through high-speed internet, and they function together like a grid. So, say you need to run a job or an analysis, you can recruit these resources from around the world to complete your job in the fraction of the time compared to what is available to you in a single data center or your personal workstation.”

He said high throughput computing breaks the computational work into smaller tasks, which can run concurrently using these resources. “Right now, we are running an analysis server and it is very under powered so basically researchers are fighting for computational space and once we get those researchers onboarded to the Open Science Grid, they can have their jobs or their analysis run within a fraction of the time,” Centino added.

Centino said they are also expanding their computer clusters to support grid capacity, but the worldwide chip shortage caused by the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions delayed the process of acquiring the servers. “So, we are looking to launch early next year for the computer cluster, around the first quarter,” he said.

The OSG has over 100 participants that provide access to large computing resources. The most notable ones include the Large Hadron Collider Beauty Experiment, the Fermi Natural Accelerator Lab (Fermilab), and Dark Energy Survey.

Study explores evolutionary stability of coral photosymbiosis

A study by University of Guam researchers has examined the evolutionary stability of photosymbiosis in scleractinian corals. The study, which was funded by the university’s National Science Foundation EPSCoR grant, was published in September in the peer-reviewed Science Advances journal.

Scleractinian corals, also called stony corals, are the hard corals that are typically seen as reef-building corals found in shallow, tropical waters that receive nutrients from the photosymbiotic algae living in their tissues. In exchange for nutrients, the algae support the calcification of coral skeletons, encouraging the growth of expansive reefs in shallow tropical and subtropical waters. Photosymbiosis is a type of symbiotic relationship between two organisms that includes one that is capable of photosynthesis.

However, half of the order’s members are non-photosymbiotic and tend to be small, not colonial, and are found in deep waters.

“The origin of the order has been shrouded in mystery. When scleractinian corals first appeared in the fossil record, they were already highly diversified,” said lead author Jordan Gault, a UOG alumnus who wrote the paper for his master’s thesis. “There’s evidence that some of them were photosymbiotic, but where did they all come from? If they’re diversified already, there’s evolutionary history that goes further back that you cannot see in the fossil record yet. That’s one thing we’ve set out to understand with this study.”

The study reconstructed the evolutionary history of photosymbiosis in Scleractinia by applying mathematical models to phylogenetic trees, which are diagrams that show evolutionary relationships. The phylogenetic trees included 1471 of the 1619 recognized species in Scleractinia.

“There are certain groups where the association seems to be almost irreversibly stable. Those two partners are bound to each other for the whole group and they thrive and die together while others may be more flexible,” said UOG Associate Professor Bastian Bentlage, the co-author of this study. “There may be some lineages – if they’re not as tightly integrated with the photosymbionts – that may be less susceptible to a breakdown of these relationships. That’s really cool in terms of understanding the dynamics of what we see on our reefs in a changing climate.”

At first, the project faced delays because the initial simulation studies took a long time to run on the computational resources that were available at the time. To address these issues, the research team used the Open Science Grid, a network of computers spread nationally that allows open access to high throughput computing for research in the U.S.

“Facilitating this study meant relying on this grid that was able to run hundreds of thousands of individual simulations,” said Bentlage. “That wouldn’t have been possible with a desktop computer. Having access to this high-speed computing grid was very essential to finishing it off.”

As part of the Guam NSF EPSCoR’s strategic plan, the program is working on establishing a computation hub at UOG.

Prior to pursuing a doctoral degree at the University of Oldenburg, Gault spent eight years at the UOG Marine Laboratory pursuing his thesis research and working for the long-term coral reef monitoring program. He said that getting the paper published feels like closing a chapter in his life.

“It’s nice and a little bittersweet. I’m proud of the work that we did and I’m happy to have it out there. The question is now: is it useful for other scientists? Does it matter going forward? The best outcome is if it somehow shapes some research down the road. If people address our results and ask questions further down the line, I think that would be excellent,” said Gault.

EPSCoR researcher participates in a collaborative paper on genetic data recording

A report that brought together researchers all over the United States highlights the need to address gaps in data recording to improve biological diversity monitoring across the globe.

Justin Berg, a University of Guam EPSCoR graduate research assistant, collaborated with other researchers to produce the paper, “Poor data stewardship will hinder global genetic diversity surveillance.” PNAS published the brief report in July this year.

For the study, the researchers looked at publicly available data in the International Nucleotide Sequence Database Collaboration (INSDC). The study notes that most scientific journals require authors to archive their genetic data in a permanent database, and the INSDC is the leading repository of raw genomic data.

With the available data in the INSDC and other open-access repositories, the study notes that researchers can now “genotype thousands of loci or sequence whole genomes from virtually any species.”

During the research process, Berg said they found gaps or missing metadata in these data sets, or it indicated different geographical locations. According to Berg, as of October 2020, the Sequence Read Archive of INSDC contained 16,700 unique wild and domesticated eukaryotic species and 327,577 individual organisms. He said only 14 percent of the genomic data had spatiotemporal metadata for genetic diversity monitoring.

Berg said, “That essentially means when people place their genetic sequences in a database, from an international level all the way to the United States NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information), they may be missing data sets and missing metadata that are concurrently in past or current studies. Right now, through this project, we show that 86 percent of these projects were missing some form of metadata, including the year that it was collected or the location where it was collected.”

According to the report, the researchers looked at aquatic and terrestrial domesticated species recorded in the INSDC through the NCBI because biodiversity studies mostly focus on these targets.

The report notes that, in principle, these data can “provide time-stamped records for genetic diversity monitoring, to support the goals of the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD).” In addition, the data can be used to shed light on “the evolutionary and ecological processes that shape biodiversity across the globe.”

As an instrument for sustainable development, the CBD focuses on the conservation of biological diversity, the sustainable use of its components and the fair and equitable sharing of the benefits arising out of the utilization of genetic resources.

“This study can help with genetic diversity monitoring through the United Nations Convention on Biological biodiversity. It can do this by including increased metadata in the future. So, if someone from another part of the world wants to go in, anyone can access this genetic data,” Berg said.

Berg and the other researchers said they join others in calling for ambitious goals to safeguard genetic diversity and the knowledge structures that will support this goal. “Common to proposed genetic diversity monitoring agendas is a shared vision whereby agile pipelines would intake raw genomic data and produce outputs that directly inform conservation policies and decisions,” the researchers said.

The researchers emphasized that without appropriate archival genomic data that include the spatiotemporal metadata, crucial information will be unavailable to such pipelines, and researchers will be unable to monitor genetic biodiversity or reconstruct past baselines.

Berg said they are planning to release a more comprehensive report on their findings.

The paper can be accessed through PNAS, a peer-reviewed scientific journal.

UOG study to examine genetic connectivity of fish, snails, and shrimp native to Guam and Marianas rivers

In an effort to manage and conserve diadromous fish, snails, and shrimp that are native to rivers in Guam and the Marianas, a researcher from the University of Guam will be working over the next four years to collect and genetically analyze species found in the region’s watersheds.

Diadromous animals are those that transition between freshwater and saltwater environments at different stages of their life cycles.

“Effective conservation management of these aquatic communities starts with discerning their historical genetic connections and/or isolation,” said Associate Professor Daniel Lindstrom, who holds a doctorate in zoology and is overseeing the project.

The work is being funded by the university’s National Science Foundation EPSCoR grant.

Nature of diadromous animals

Many of the fish, snail, and shrimp species that live in the streams of Southern Guam are spawned in freshwater before drifting into the ocean as larvae before migrating back to freshwater to grow into adults and spawn.

“When the eggs of these species hatch, they get washed out into the ocean,” Lindstrom said. “There is a possibility that the animals you find in freshwater in the island region may all be connected because of this larval marine phase.”

‘Rewriting the book’ on these organisms

Lindstrom plans to collect specimens from each of Southern Guam’s 14 main watersheds and then eventually expand to Saipan and Rota to augment the collection. An initial collection has already been conducted in the Asmafines and Sella Rivers.

As the specimens are collected, they will be photographed, dissected, and then undergo DNA extraction.

“By looking at the genetics of these animals, I can check how similar they are to the same species found in another river on Guam and check the genetic similarity to see the patterns in their population,” Lindstrom said. “Even though those two rivers flow into the ocean less than 50 meters apart, they have different species in them. That’s really strange and I hope our genetic and survey work will find answers for that.”

He is targeting approximately 60 species that have not been genetically confirmed as existing or distinct species and have been referred to with tentative names or listed only by genus but without a species name.

“There’s an ancient Chinese proverb that goes: ‘The first step on the path to true knowledge is getting the names of things right,’ so I’m really excited about that, and I’m hoping that’ll be my scientific legacy on Guam,” he said. “We’re pretty much rewriting the book on the island’s native diadromous organisms.”

Potential to discover new species

It’s possible the research team — including EPSCoR-sponsored graduate students Khanh Ly and Karina Mejia and undergraduate student Louise Pascua — may uncover a few new species along the way.

“I’m excited to see what species we can describe and to find new species – whether they’re here or on other islands,” Ly said. “I’d like to publish research about them for other people to use.”

This project will contribute to 30 years of collecting and genetically analyzing specimens from watersheds all over the tropics, including Guam, Saipan, Rota, Hawaii, Japan, the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, Panama, Costa Rica, and Nicaragua.

All of the preserved specimens and tissues collected over the course of the project will go to the GECCO Biorepository, a physical and cyber warehouse of records and images operated by the Guam NSF EPSCoR program. The biorepository can be accessed online at https://specifyportal.uog.edu/.

Diatom herbarium upgrades archival equipment for long-term accessibility

The diatom herbarium, which is part of the University of Guam (UOG) Herbarium and the Guam Ecosystems Collaboratorium for Corals and Oceans (GECCO) Biorepository is getting new, archival labels in recognition of its permanent value as a repository of diatom samples from the Marianas. The GECCO Biorepository is a physical and cyber warehouse of records and images that is operated by the Guam NSF EPSCoR program, which is funded by the National Science Foundation.

Diatoms are microscopic single-celled algae found in oceans, lakes, and rivers.

“Diatoms produce two-fifths of the oxygen we breathe and are used as water quality indicators in freshwater studies,” said UOG Professor Emeritus of Biology Christopher Lobban. “But for the marine species to be useful as indicators, we first have to find out what species live here and under what conditions.” The collection is a legacy project that was started by Lobban in 1988 and includes samples collected in Guam, Yap, Chuuk, Pohnpei, Palau, and the Marshall Islands. The collection was paused for nearly two decades, but was rekindled in 2007 when new equipment, collaborators, and online access to old literature became available.

As the project grew, it became apparent that it needed to be curated as a collection for long-term accessibility. Once the self-sticking slide labels from its start in 1988 began to fall off from age, Lobban found best practices for museums and acquired archival paper, special adhesives, and custom templates to catalog 3,000 existing slides and label new slides.

“If the slides are to be useful in the future the labels need to stay on,” said Lobban. “The label indicates the sample number, which refers to the collecting information in the lab notebooks and database. Not knowing where and when the samples were collected significantly decreases their scientific value.” There are over 3,300 slides and 1,600 scanning electron microscope stubs, along with raw materials and remainders in the diatom herbarium, which is located in the Microscopy Teaching and Research Lab.

The list of cataloged materials has been entered into the Guam NSF EPSCoR Biorepository online database. A long-term project is underway to get all of the imaged specimens added along with their images. The online database can be accessed at https://specifyportal.uog.edu.

Study will identify traits that make coral species resilient to climate change

As the planet experiences heatwaves, warming seas, and other effects of climate change, researchers from the University of Guam (UOG) will examine how these impacts may affect the structure of the island’s coral reefs by identifying species-specific responses to environmental change.

The experiment, which is being funded by the university’s National Science Foundation EPSCoR grant, will study three habitat-forming coral species that are dominant throughout the island’s shallow reef flats, two of which exist in distinctly different color morphologies. These species include: the boulder-like massive Porites, which grows in both brown and purple morphologies; the fingerlike Porites cylindrica, which grows in brown and yellow morphologies; and the staghorn coral Acropora cf. pulchra. Cuttings of each coral species and color morph were planted in four plots in two sections of the Piti Marine Preserve and will be monitored for the next four years.

“We hope to learn about which of these species and their color morphs have characteristics that may confer better resilience to climate change,” said Professor Laurie Raymundo, the interim director of the UOG Marine Laboratory. “That will allow us to examine why they’re doing better and why some of them aren’t doing as well. Eventually, we may be able to make some predictions about how Guam’s reefs may change in the future.”

This project is unique because many studies are conducted within a much shorter time period.

“In most cases, people conduct an experiment for a whole season,” said UOG Associate Professor Bastian Bentlage. “There are not a lot of datasets – especially over

a multi-year span – that look at individual corals and really provide data on how they get stressed, and recover, and follow the long-term effects of experiencing that stress.”

The plots will be checked biweekly during the bleaching season from July to October and monthly from November to June, when sea surface temperatures are cooler.

The data collected from this experiment will be used by a team of mathematics professors and students at the university to model disease transmission and responses to stress, to better inform reef management and intervention strategies.

“We hope to gain a better understanding of what Guam’s reefs will look like in the future and what kind of traits lend themselves to coral resilience so that we can implement control measures that will result in a healthier coral reef ecosystem,” said UOG Associate Professor Leslie Aquino. “We’re really seeing the benefits of this cross collaboration between the Math and Marine Laboratory teams and sparking new ideas and better understanding for both groups of how these models and coral reef ecosystems work.”

New reefs

At the end of the experiment, each of the plots will be left to grow into new reef assemblages as part of a permit agreement with the Guam Department of Agriculture. Monitoring beyond this project may continue to contribute to an even longer-term data set that can continue to inform management.

During the initial planting of the coral cuttings, Bentlage noticed that young fish were attracted to and visiting the plots. According to a study based in Fiji, juvenile fish are able to smell the difference between good and bad reefs.

“I still think that was one of the coolest, most eye-opening things,” said Bentlage. “It was really interesting to see how it attracted the fish community that now seems to be resident in these plots. I hope that I can come back five to ten years from now and see how our experimental plot turned into the seedling of a new reef track.”

Biorepository receives coral collection from UOG professor emeritus

The Guam EPSCoR Guam Ecosystems Collaboratorium (GEC) Biorepository is welcoming its largest addition yet – a private collection of around 30,000 coral specimens from University of Guam Professor Emeritus of Marine Biology Richard Randall.

The collection includes specimens from Guam and other places throughout the Pacific and reflects the 56 years since Randall joined the UOG Marine Laboratory, which he spent researching coral reef biology and geology.

During the late 1960s, Randall witnessed the first crown of thorns outbreak on Guam and managed to retrieve a few coral samples before they were eaten. He claims some of these specimens may be new species and others may not exist today.

“He took meticulous field notes, so we have really good data about each of these specimens,” said David Burdick, the biorepository’s collections manager. “He also recorded an unusual amount of data like where it was living, its name, and how much light it was exposed to and how that may have influenced its shape. That information can help us understand their habitat requirements and discern between similar species.”

So far, the facility has received less than a tenth of the collection’s specimens and may take years to catalog each item and upload them to the biorepository’s website.

“Right now, we’re going through all of the coral specimens and cataloging the ones we have with the specimen number he gave them and the notes that connects them to the specimen,” said Kelsie Ebeling-Whited, the biorepository’s technician. “We log the

specimen number, the note number, its species, and family. We want that all in a database so that we know what corals we have.”

Once the collection has been processed, it will serve as a resource for researchers around the world to better understand the diversity of the corals found in the Pacific.

“It’s going to be a lot of work,” Burdick said. “In some cases, if he’s described a new species, we’d have to publish it in a book or a journal about it. I feel like we’re always trying to play catch-up trying to understand more about these organisms before we lose some of them. It’s an impressive collection that’s really important for us to take care of and share with the world and try to use it to provide an impetus for collaborative research.”

About the biorepository

The Guam EPSCoR-GEC Biorepository serves as a world-class physical and cyber warehouse of Micronesian marine biodiversity enhancing local research capacity and facilitating collaborative research through global access to specimen records and images. The facility is operated by the Guam EPSCoR program, which is funded by the National Science Foundation. The online collection database can be accessed at https://specifyportal.uog.edu/.

Column: Hunger games on Guam’s reefs

World Reef Awareness Day on Tuesday provides a great opportunity to spotlight the unique natural heritage of Guam’s reefs and the strong cultural connection of the CHamoru people to this valuable resource.

In recent months, juvenile rabbitfish (mañahak) have traveled from various Micronesian islands to Guam and are now quarantining on the island’s reef flats. Much like our own children, these youngsters have an insatiable appetite and can curtail seaweed gardens on reefs where they couch surf.

In Pago Bay, extensive stands of the angel hair seaweed, a species that has been proliferating on Guam’s reefs since 2012, have now been decimated by these rabbitfish. This is a fine example of the biological control of a nuisance species without human assistance.

Stonefish in seaweed camo

Mañahak are not picky eaters and they happily feast on the diversity of seaweeds that reefs have to offer. The impact of the rabbitfish raid was striking when I was desperately searching for seaweed during a recent field trip in Pago Bay.

When a boulder generously covered with bright green tufts of seaweed caught my eye, I thought I had struck gold. While plucking off these tufts, the boulder suddenly aroused and charged off at a whipping speed. The two eyes on the boulder glanced back and I realized that this huge stonefish had capitalized on the existing food scarcity by using seaweed camouflage to deceive its rabbitfish prey.

Mass spawning

Some seaweeds are untouchable by grazing fish. Vivid green clumps of turtleweed (Chlorodesmis fastigiata) stand out on reefs but are not targeted by herbivorous fish because they contain toxins.

Like rabbitfish, turtleweed releases offspring en masse when the conditions for their survival are optimal. Rabbitfish runs have evolved into seasonal events that coincide with the main growing season of seaweeds.

Turtleweed is more selective in timing its reproduction. Episodes of mass spawning by this seaweed occur when bare patches of reef become available in the aftermath of storm events. At that point, turtleweed is fully committed to reproduction and the whole seaweed is converted into reproductive cells after which the parent plant dies.

Faking a poisonous appearance

The camouflage trick of stonefish is topped by the disguise-by-resemblance (mimicry) strategy of the Piti Bomb Holes seaweed (Rhipilia coppejansii). Guam is home to several species of Rhipilia, which all form distinctive spongy blades.

The Piti Bomb Holes seaweed is only found on Guam and is unique in forming green tufts of loose filaments that resemble turtleweed. The chemical composition of the Piti Bomb Holes seaweed is as of yet unknown, but its apparent similarity to poisonous turtleweed might ensure its survival on reefs where herbivores abound.

Cultural traditions

Humans have become part of the natural dynamics on reefs. The mañahak season brings people together while catching, processing or feasting on this seasonal culinary delight. Observant fishermen are the first to witness the changes that are taking place on reefs. They have already adapted by using the overly abundant angel hair seaweed as fishing bait or as a crispy and tasty additive to salads.

Even in this day and age of magnificent nature documentaries and well stocked grocery stores, it remains important to celebrate and perpetuate cultural traditions that are deeply rooted in the island’s natural heritage. After all, such activities allow us to evaluate the health of our ecosystems and find solutions for environmental issues specific to Pacific islands.

Tom Schils is an EPSCoR Researcher and a professor of marine biology at the University of Guam with a research focus on the diversity and ecology of seaweeds in the tropical Pacific. He can be reached at 735-2185 or tschils@triton.uog.edu.