Scientists from Tulane University’s Biodiversity Research Institute (TUBRI) collaborated with the University of Guam NSF EPSCoR Biorepository in April, leading a series of workshops focused on biodiversity technologies.

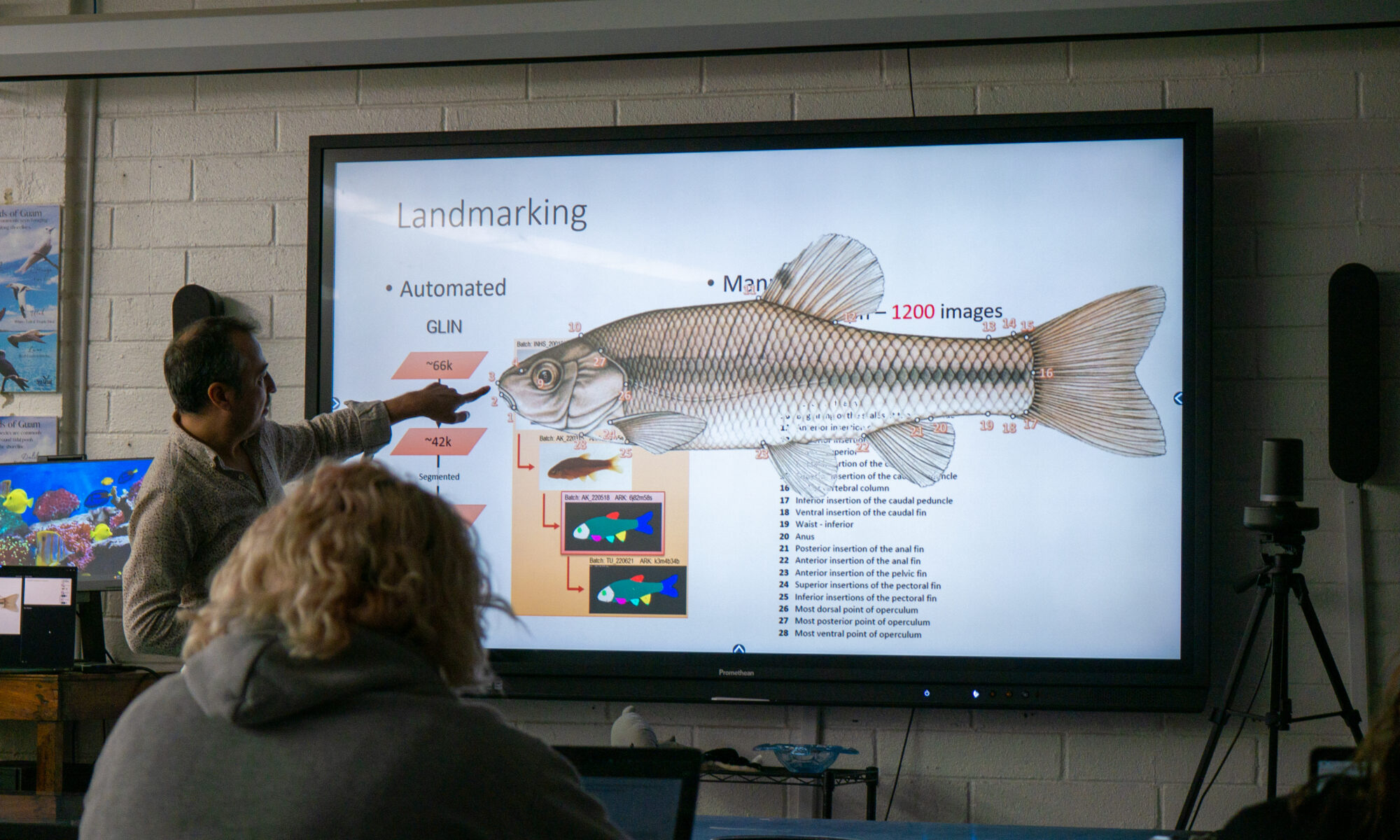

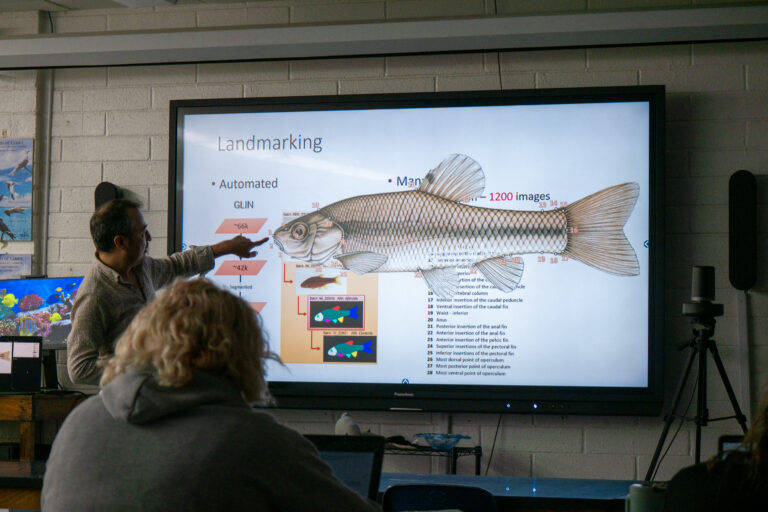

Hank Bart, Ph.D., director of TUBRI and professor of ecology and evolutionary biology and Yasin Bakiş, Ph.D. senior manager of biodiversity informatics, covered TUBRI-developed technologies, including the use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in processing biological data and fish collection management software. The two TUBRI scientists also toured the university facilities.

“We do biodiversity informatics research and a lot of it is technology for how you can study organisms or infrastructure that you need to store data about organisms – databases, things like that,” said Bart.

“So what we hoped is that there’ll be opportunities to work together for setting up a database for collections, collections in the bio-repository but also other kind of technology they would need,” he added.

Bakiş agreed and added that one motivation for visiting with other institutions is the ability to collaborate in order to develop tools that can be used by other researchers.

“Rather than give them a presentation about what we are doing, it is like brainstorming actually,” said Bakiş, noting that their presentations usually include a lot of time for questions and discussions. “So when we go back home, we bring all those questions with us and we improve our tools and our information systems. It helps a lot.”

One of the main topics of the workshops was Imageomics, a new field of study that involves AI and machine learning to extract biological information directly from images that can turn collections of photographs into databases about organisms and provide insights on many areas of biological research. This has the potential for many uses including species identification, understanding morphology and enumerating samples of microscopic orgasms such as diatoms.

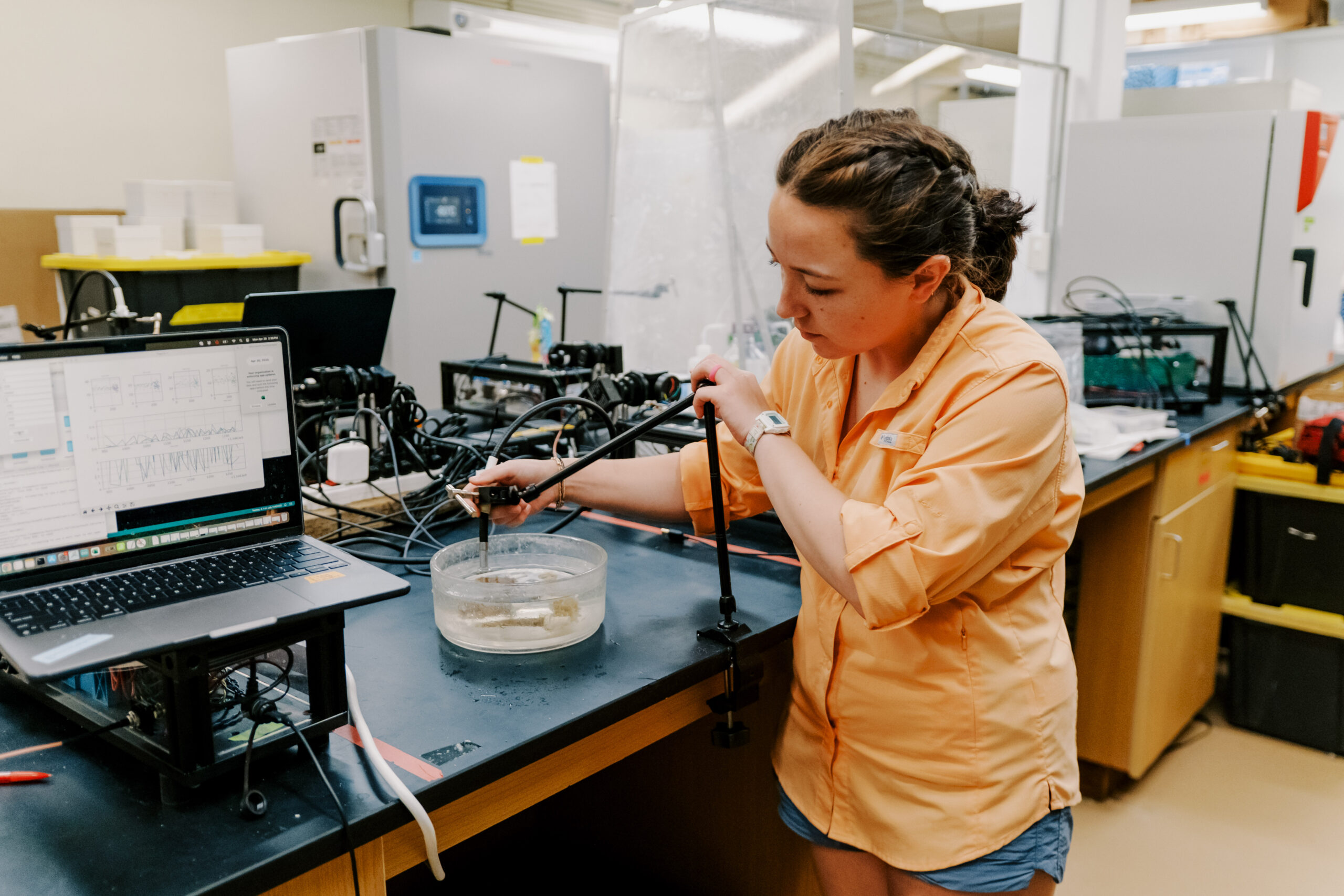

Following the visit Dave Burdick, Guam NSF EPSCoR Biorepository research associate, said he is interested in the potential benefits of utilizing machine learning for biodiversity research and working on ensuring Biorepository data is ready for AI applications. He believes that establishing and continuing a relationship with TUBRI can help improve the processing of Biorepository specimen data for these purposes.

“By making sure tropical western Pacific fish species are represented in images and data sets that train AI algorithms we can increase the effectiveness of those AI tools for the species in our waters,” said Burdick. “Ultimately, making our images and specimen data more ‘AI ready’ will help make the AI tools more useful for us down the road, as those AI tools will likely allow small teams like ours increase the scope and efficiency of regionally focused biodiversity research.”

Due to the rich variety of organisms found in our region, the Guam NSF EPSCoR Biorepository is home to thousands of specimens of marine organisms – many of which are still being identified to this day.

“In high diversity areas like the Mariana Islands there is much to be discovered, and much to learn about the species already reported here,” said Burdick, “so we’re always looking for ways to do the work more efficiently and effectively.”

Through this blossoming relationship with TUBRI, it is possible that developing technology may be used in the future to help identify organisms and organize data to more easily make that information accessible to the public.